Greg Tinsley

Until roughly 60 years ago, the prehistoric technologies of the bow and arrow lay mostly frozen among the bones of mastodons. There were very few bowhunters around to notice or care.

Lightly sprinkled from Alaska to Florida, who knows the actual number of hunting archers in 1965? Eighty thousand? A buck-sixty? Whatever the amount, a good many of them were enjoying the solitudes of special archery seasons, recent opportunities that the modern pioneers of bowhunting had pressed from state wildlife agencies.

Led by the radical conservation efforts of the American hunter, the continent’s shot-thin deer populations were just then spiraling upwards to historic proportions.

While incremental deer and an increasing supply of Archery-Only seasons represented the elite catalyst for bowhunting, the endeavor’s revolutionary change agent was the compound bow, invented in 1966 (patented in ‘69) by an obscure Missourian named Holless Wilber Allen.

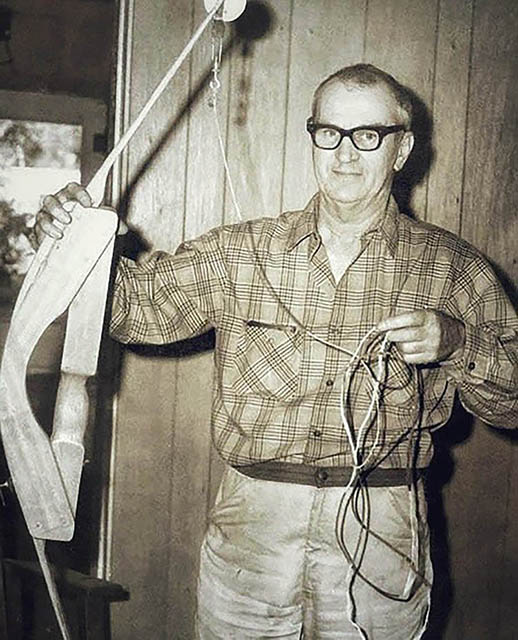

The unhappiness Allen felt as his arrows were sidestepped by twitchy whitetails had driven the visionary just mad enough to saw the limb tips off of a perfectly good traditional recurve bow. He transplanted a pulley system to those ruins, providing a decadently mechanical, All-American solution to a problem long abandoned by the ancients.

This brilliant “Allenstein” that emerged from his shop was roundly criticized as an abomination. Undeterred, the inventor brought Tom Jennings to the discussion, one of the most dazzling recurve bowyers of the day. For Jennings, the Allen bow was a rapture.

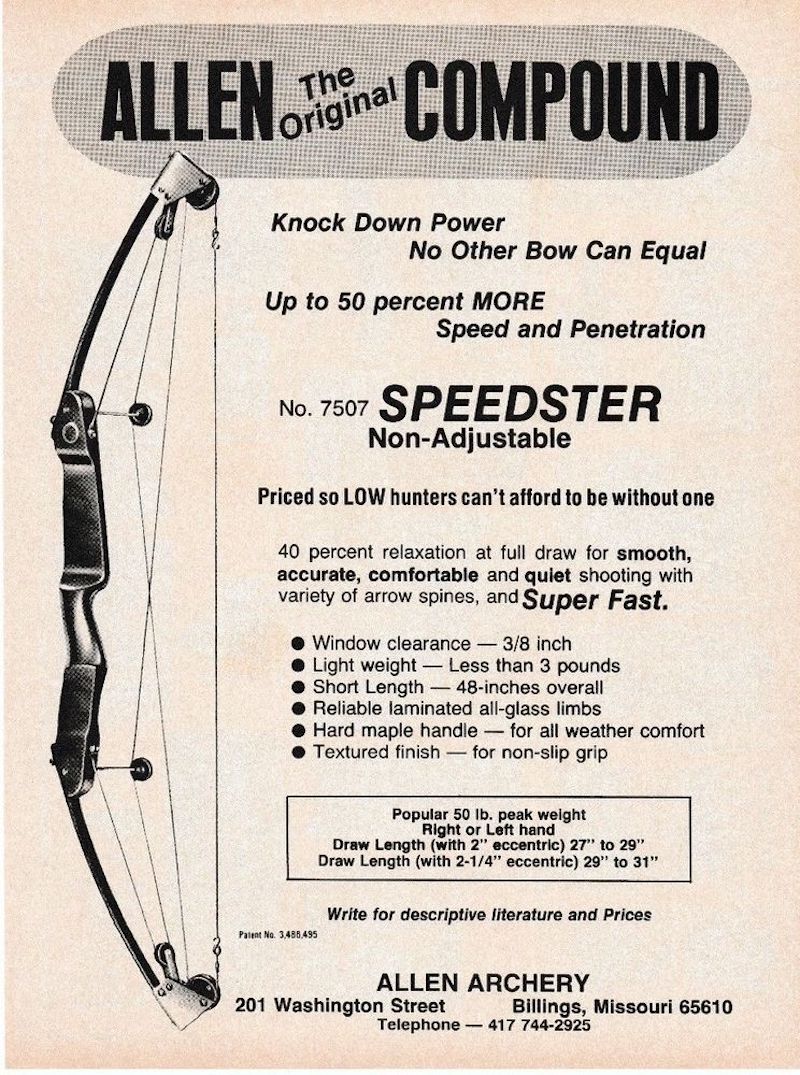

Allen went to market in ’67 with the Allen Compound, a mosh pit of hanger brackets, cams, idlers, nodes and like seven feet of cabling. Topline promo for the Allen bow included: “Knock-Down Power No Other Bow Can Equal. 40-Percent Relaxation. All-Glass Limbs.”

With even more letoff, Jennings Archery unveiled a compound bow in 1974, a simplistically reimagined product called the Model T. Astraddle the company’s Big Western promotional vibe, the T electrified the great hunting-bow reset. All of which seemed completely copasetic until Allen perished as the result of a car crash in 1979.

Per his Archery Hall of Fame credentials, Jennings had been issued license #1 to manufacture and sell compound bows under the protection of the Allen patent.

Nevertheless, regarding his use of Allen’s original intellectual property – now without Allen’s personal input to the matter – Jennings lost a tedious legal battle a few years later, and bowhunting’s chief firebrand was essentially extinguished where it stood. Legend is that Jennings closed his West Coast bow factory from the courthouse payphone.

Surviving such backstage intrigue, it is believed today that there are 3.7 million bowhunters in these United States. Target shooters and youth must push the total-archery set to within sight of 5 million participants. Neither Allen, nor Jennings, would be much surprised by any of that to include the design technologies, the materials and the precision manufacturing baked into the top-end compounds of the 2020s.

Allen and Jennings might agree that parallel bow limbs are the best thing to happen to compounds in more recent times. Finely tuned to a quality arrow – launched with a mechanized release aid from a deep valley of letoff – it seems that this parallel-limb configuration finally quantifies the formula for the sweet-shooting, keyhole accuracy that today’s well-practiced hunting archers demand.

When I hear these great things about the ultra-compound, I cannot help but remember the gentleman-genius who I knew Tom Jennings to be. My favorite recollection:

We were tucked into the desert hills of Southern California, alone in Tom’s dirt-floor quonset- hut bow lab. The year was 1988. The beam of a spotlight shown on a fully drawn prototypical compound braced vertically in a custom bow press. He nodded to it with those piercing eyes and that trademark Mississippi gambler cowboy hat of his, eyes aglitter through smudge-dusted, unleveled spectacles.

“I’m working on 90-percent letoff,” he shrugged, recognizing my eye-popping shock at such heresy.

With that enormous and welcoming Tom Jennings smile, he added, “One-hundred-percent letoff is theoretically possible, but I’m not sure how it will shoot.”