Greg Tinsley

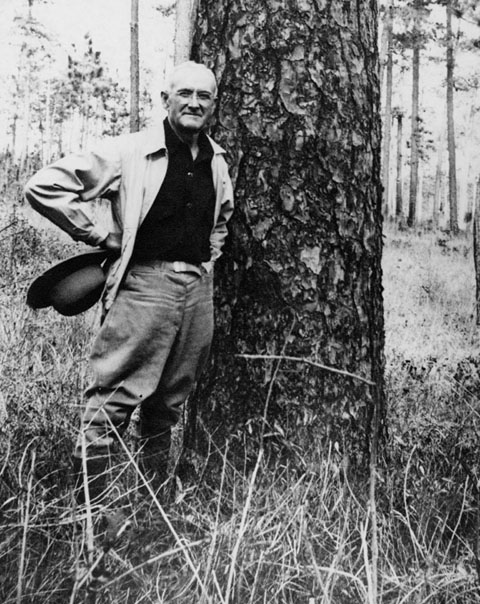

While the person charged with keeping the hippopotamus warm and alive in Maraboo, Wisconsin likely suffered an unemployment event, it was exactly the preponderant death of that hippo in the winter of 1910 that seemed an act of God’s grace for Herbert L. Stoddard.

As the massive beast was processed for transport to the Milwaukee Public Museum, Stoddard’s determination and dexterity with skinning knives impressed the museum’s traveling chief-of-taxidermy George Shrosbree, who offered an apprenticeship on the spot to the 21-year-old.

For several years thereto, young Stoddard had been a laborer on the Wisconsin farm of Herman Wagner. In winters, under a paid-study/non-compete gentlemen’s agreement, he worked for Ed Ochsner, the region’s master taxidermist. Ochsner was a well-connected artist and businessman. The dead hippo belonged to his hunting buddy, Alfred Ringling, of the Ringling Brothers Circus.

Born in Illinois in 1889 – and without the benefit of finishing high school – the professional scientific career of Herbert Stoddard was fueled by work outdoors rather than classroom studies. Starting at age seven (7), these campuses of hard knocks for Stoddard included:

The Pine Barren cow camps of the Florida Panhandle. There, Stoddard witnessed cattlemen utilizing the ancient technique of prescribed burning, and the resultant regeneration of wildlands cleared of understories through the therapeutics of fire. Controlled burns would eventually become one of Stoddard’s professional authenticities.

“No schooling or advantages could have been more valuable to me, in my later years as ornithologist, ecologist and wildlife researcher," he would say of his time in the Red Hills with the old cowboys, camped among the virginal longleaf pine savannas of the Florida-Georgia hinterland.

Read More: AMERICA'S FIRST FEMALE CONSERVATION OFFICER

"Herbert Stoddard, in Georgia, started the first management of wildlife based on research," Aldo Leopold, the man regarded as the father of American wildlife management, would later confide.

Stoddard traded his first three years with Shrosbree at the Milwaukee Public Museum (MPM) for seven more at Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. He returned to MPM in 1920 with the idea that field collection and ornithology, rather than taxidermy, was to be the essence of his life’s work. Two years later, he had shifted his expertise to bird conservation, helping organize the Inland Bird Banding Association during the 1922 meeting of the American Ornithologist's Union. For MPM, Stoddard began bird banding, publishing stories for science journals and investigating native and non-native species. He was first to document the invasive presence of the European starling to the Americas in 1923.

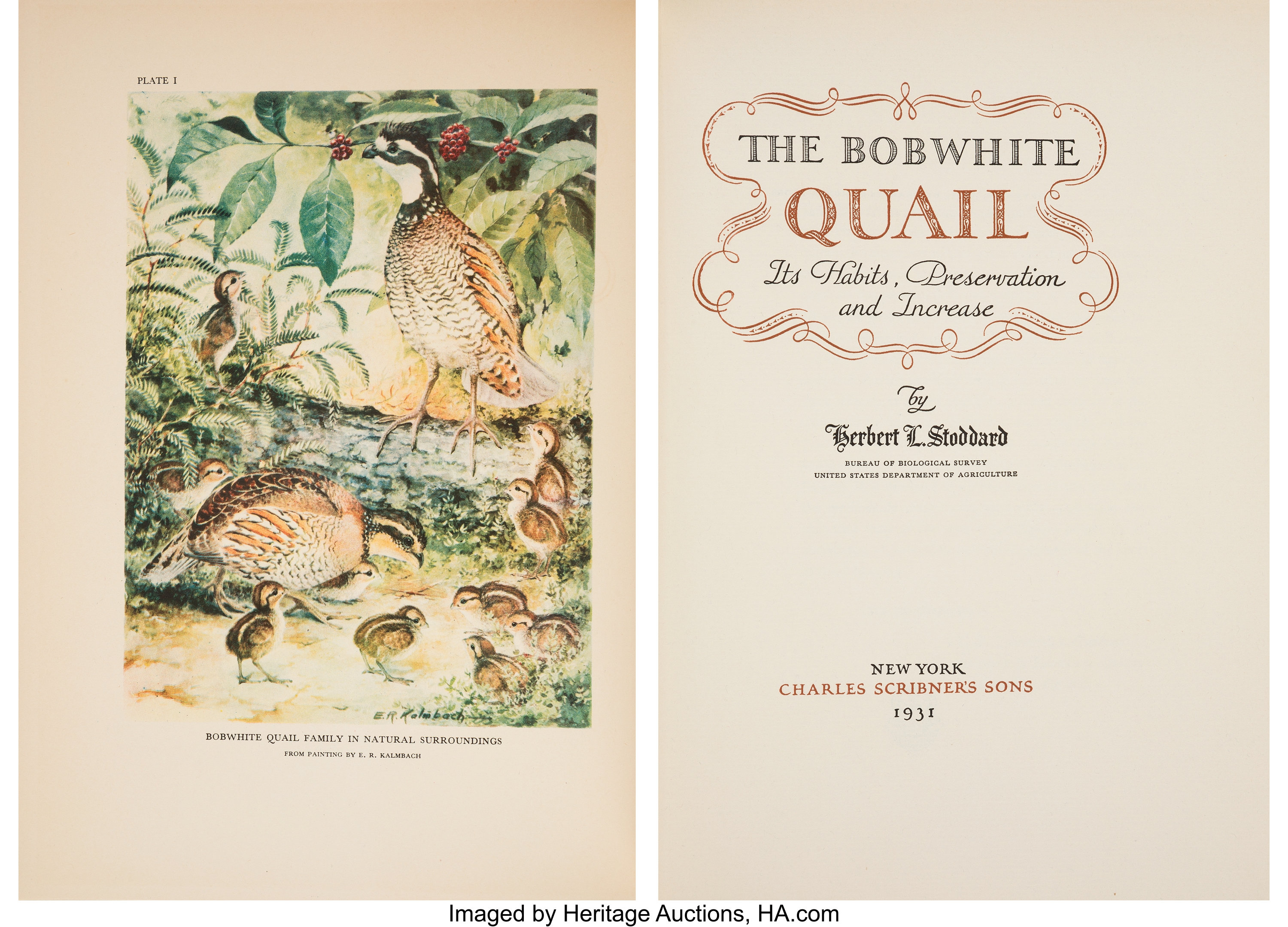

The U.S. Bureau of Biological Survey (eventually, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) recruited Stoddard in 1924 to troubleshoot alarming declines of bobwhite quail in north Florida and southern Georgia, the unique Red Hills uplands of his cowboy youth. Stoddard’s Cooperative Quail Investigation was supplemented by local landowners – collectively, the wealthiest quail hunters on earth. And by 1931 his management recommendations were in play there.

He soon completed “The Bobwhite Quail: Its Habits, Preservation, and Increase” – a book of scientific gospel concerning the perpetuation of Southeastern gamebirds. He also formed the Cooperative Quail Study Association and co-founded the Tall Timbers Research Station near Tallahassee.

Editions of "The Bobwhite Quail: Its Habits, Preservation, and Increase" are out of print and now sell for several hundred dollars.

The forest management plan he began devising in 1950 with Leon Neel, a graduate of the University of Georgia, became the ultimate model of the longleaf-wiregrass region. The Stoddard-Neel Approach utilizes hyper-selective logging, which results in a forest structure of age-diverse trees. Understories are principally controlled by prescribed fire, with tree-harvest selection aimed at sustained yield and aesthetics. The open, parklike nature of these magnificent forests harken the lyrics of William Bartram, an early explorer, who wrote: "...a forest of the great long-leaved pine, the earth covered with grass, interspersed with an infinite variety of herbaceous plants, and embellished with extensive savannas."

Stoddard’s near-block observational experiment on the effect of fire frequency, and its relationship in controlling nuisance variables, remains a study in-progress to this day.

It had become known by the 1950s that vertical man-made super structurers of every description were indiscriminate killers of birds in flight. But just how bad was that problem? Near his office in 1955, Stoddard launched a breakthrough inquest beneath the new television transmission tower of WCTV. He and his assistant, Robert Norris, and many others, collected evidence there seven days a week for 28 consecutive years.

The Herbert Stoddard sphere of scientific influence is worldly. He often used a VW Beetle with an optional sunroof as a mobile observation platform during his bird-mortality study at the WCTV transmission tower.

The volume of research produced a global shockwave:

On a single day – September 19, 1962 – more than 800 birds were killed at the antenna site. The lone antenna and its rigging would kill more than 44,000 birds of 186 species during 336-month study. Regarding bird mortality, communication towers are today less lethal thanks to Stoddard, though man-made structures continue to rank among the world’s top killers of birds.

Read More: Aldo Leopold, The Oracle of American Conservation

As academia continues to warn of the inexplicable 25-percent decline in world bird populations, as landscape-size wind farms and water-mimicking solar arrays replace oilfields, Stoddard’s lethality report regarding man-made structures is notable, if not obscure, science.

In reverse order of importance, in his lifetime Stoddard received the William Brewster Memorial Award from the American Ornithological Society, the Silver Star and Letter of Commendation from Admiral Nimitz for his actions during World War II and his only son, Herbert "Sonny" L. Stoddard Jr., from his beloved wife Ada.

Naturalist, conservationist, forester, wildlife biologist, ecologist, ornithologist, author, hippopotamus skinner, decorated war veteran and the original scientific champion of low-intensity wildfire and prescribed burns--Herbert Stoddard truly old-schooled his transcendence to the pinnacle of the All-American conservation movement.