Where can you have the biggest impact?

Todd Amenrud | Originally published in GameKeepers: Farming for Wildlife Magazine. To subscribe, click here.

Over the years, I’ve heard hunters claim their rationale for not hunting a certain region, or the reason why the bucks they harvest in a given area are always small in comparison to the same age class maybe only a county away: “it’s because of poor genetics.” Out of all the examples of this, the state of Mississippi is often used because there has been a definite historical distinction in regions of Mississippi where big-bodied, big-antlered whitetails are produced, and in other identifiable areas the deer have small bodies and small antlers. In addition, the MSU (Mississippi State University) Deer Lab has probably done more research on this subject than anywhere else, however, the same holds true no matter where there are whitetails. For many years this small deer excuse was primarily blamed on poor genetics, but is this really true?

One of my mentors taught me early on that big antlers and large bodies come from the soil. From the soil, to the plants, and onto the whitetails – this is true. This basic idea was known by the very first, original gamekeepers back during Medieval Times. As far back as 1307, the gamekeepers of King Edward II said, "The head grows according to the pasture, good or otherwise."

This news isn’t necessarily hot off the press; research is always ongoing. Obviously, when it comes to free-range whitetails, the recipe for large antlers includes the ingredients of age, genetics and nutrition. We can, however, only significantly impact age and nutrition in the wild. I suppose you can alter genetics a fraction by harvesting certain animals, but in the wild, how do you know what you’ve just changed? There is no way to really impact genetics without a high fence and then controlling specifically which doe breeds which buck.

For the purpose of this piece, just so we’re comparing apples to apples, we will say that all bucks, no matter where they are located, are allowed to reach at least five years old. So whether we’re referring to high-fence deer farms or different free-range areas, in various states or anywhere on our continent, age will be a given.

“IT’S ABOUT CREATING A LEGACY FOR ALL FUTURE GENERATIONS. SUBSCRIBE TODAY.”

The question might arise, “Since we can’t control genetics, are they really that important to us free-range gamekeepers?” I would argue that with serious deer breeders, where age and nutrition are a “known,” genetics are of the utmost importance; it’s what sets the good breeders apart from the great ones. On a deer ranch like this, the herd typically receives the absolute best nutrition possible and no bucks will be harvested until they’re at least 5 or 6, so genetics is the biggest variable for places like this. However, for us free-range gamekeepers that is NOT the case.

Logic dictates that if we take age out of the variables, because remember, we’re allowing all bucks to reach at least five years old before they’re harvested, nutrition is then the only area left we can influence - albeit, it’s an area where we can have a very big impact. As free-range gamekeepers, nutrition is obviously our greatest shaping effect.

How do we know that the problem in regions of Mississippi and other areas of the country where they have traditionally produced inferior deer isn’t because of genetics? While some examples surely could be due in part to poor genetics, there have been several instances throughout the years where whitetails with larger body weights and big antlers were captured and introduced into some of the areas where small bodies and antlers had been a problem. The new genetics were supposed to breed out the problem and help boost body weights and antler size. These projects were basically a bust! There were no differences seen. The areas still continued to produce small bodies and poor antlers.

But this is how we know for certain. Eric Michel, PhD., Mississippi State University Deer Lab (who now works in my home state for the Minnesota DNR) found that nutrition is probably the biggest factor in limiting body and antler size. Using data collected throughout Mississippi, performing several studies, and using information collected over many years by the MSU Deer Lab, Michel found that nutrition clearly has a huge impact on both! In addition, it’s not just about the nutrition provided a specific animal during its life, it’s also about the nutrition the parents receive and the start it gets from its mother during gestation.

“IF YOU LOVE WILDLIFE AND WANT TO IMPROVE HABITAT, SUBSCRIBE TODAY!”

blamed; however, there have been several prime examples

throughout the years where it has been proven it’s not likely

the case. Big-bodied, large antlered bucks were captured

and introduced into areas where small bodies and antlers

had been a problem. The new genetics were supposed

“breed out” the problem. It didn’t happen - the areas

continued to produce feeble bodies and antlers.

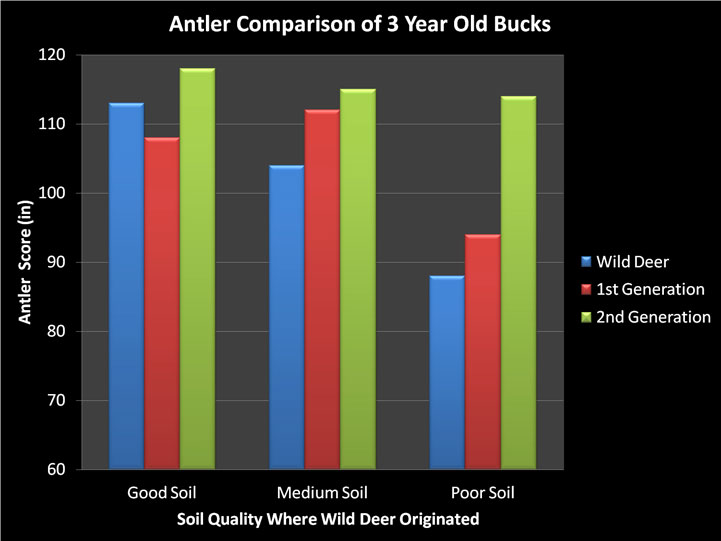

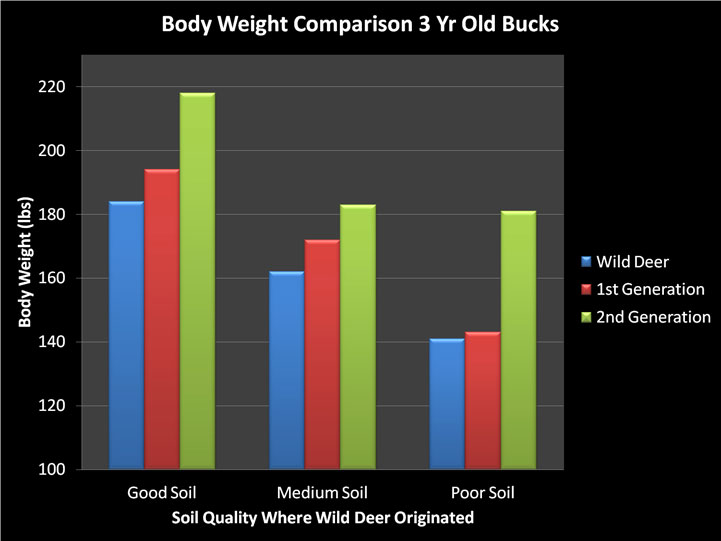

Michel first began to prove this by using harvest data from the Deer Management Assistant Program (DMAP) and data acquired from years of previous MSU Deer Lab studies (Strickland and Demarais 2000, and Strickland et al. 2013). It was found that when comparing bucks that were three years old, body weights averaged 41 pounds heavier in areas with good soil compared to areas of poor soil. In addition, antler scores averaged 25 inches more in areas of good soil.

Is it the crop/forage that makes the difference or the soil quality? There is evidence to back up both. Obviously, in areas of good soil, it’s common to see high-quality agricultural crops grown and these make up a large portion of the whitetails’ diet. In medium soil quality areas, these same cash crops are also grown, just not to the extent that they are in the good soil areas. However, in the poor soil quality areas there is a stark difference; the ground may still be used for agriculture production, but rather than soybeans you’re more likely to see a pine plantation. While poor soil can be transformed into good soil, it can take some work and may cost a bit. Areas of inferior soil tend to grow the types of crops that make feeble nutrient transfer agents.

With the help of Mississippi’s Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Parks, Eric Michel, along with many MSU Deer Lab Graduate Students, captured whitetails from numerous areas. Each area was classified as poor soil, medium soil, or good soil. The deer were then transported back to MSU, but each group was kept separate from one another – the deer from good areas were kept together, poor areas together, etc.

Every day during fawning season the pens were scoured and when a fawn was found it was weighed and tagged. The fawns were sedated and weighed again in the fall and then each subsequent year thereafter.

The animals were allowed to breed with others within their own soil classification region. So bucks from a good quality soil region were allowed to breed with does from the good quality soil region, medium with medium, and so on. The animals were allowed to produce two generations of offspring.

The first generation of fawns that were born from wild parents were given a high-quality 20% protein diet, but were still kept in their own group. The second generation of fawns that were produced from the first generation parents were also raised on the high-quality 20% protein diet.

When each generation reached three years old, data were compared. While there was an increase in body weights and antler size in the first generation (born from wild parents), there was a significant increase across the board with the second generation of fawns (born from the first generation offspring). The bucks from poor soil regions (born in the second generation), had caught up to the original wild bucks from the good soil regions! Genetics? No, nutrition!

The bucks from the first generation, from poor soil areas only had a minimal impact on body weights, but the second gen, three-year-old bucks from poor soil areas had a huge increase with an average weight boost of 35 pounds! Antler size did better with the first gen, poor soil bucks, with an average increase of over 10%. But the second gen, poor soil bucks increased antler size around 25% over the original, wild bucks! After improving nutrition, the playing field had been leveled! Antler size on the second generation bucks from the poor soil area had caught up to the original wild bucks from the good soil area…and genetics had little or nothing to do with it.

“BECOMING A GAMEKEEPER IS NOT JUST THE BEST WAY TO PRODUCE GREAT HUNTING… IT’S THE BEST LIFE! SUBSCRIBE TODAY.”

Another important note; just because you have good soil, doesn’t necessarily mean your herd is gaining full advantage of it. Even with the animals that originated from areas with good soil, when nutrition is emphasized it can have a vast impression on future generations. Even with the good soil bucks, body weights increased approximately 20% from the original wild generation to the second generation (born from the first generation parents). That’s huge!

So what does this tell us? Clearly, it really is all about nutrition and your soil quality. It also tells us that if the parents (especially the does) have poor nutrition, their offspring will likely always be inferior. It also demonstrates that just because you have good soil, it doesn’t mean your herd is able to take full advantage of it. Thought must be put into making the nutrients available through proper crop selection and management of the native vegetation so the nutrition can make it to the deer.

This piece cites studies done by the MSU Deer Lab, but the principals hold true no matter where whitetails roam. It bewilders me that most people who plant food plots do it mainly for attraction during hunting season. With proof like this (antler size increase of 25% or more), I don’t know why every gamekeeper wouldn’t also want to plant for nutrition, too! By improving your soil and making your crops and the native vegetation the best nutrient transfer agents possible, you can have a huge impact on body weights, antler size and the over health of the deer in the area, no matter whether you’re in Mississippi, Missouri or Manitoba.