Ryan Graves

1848- 1933

Senachwine Lake, Illinois; Chicago, Illinois, Pascagoula, MS, and Houston, Texas

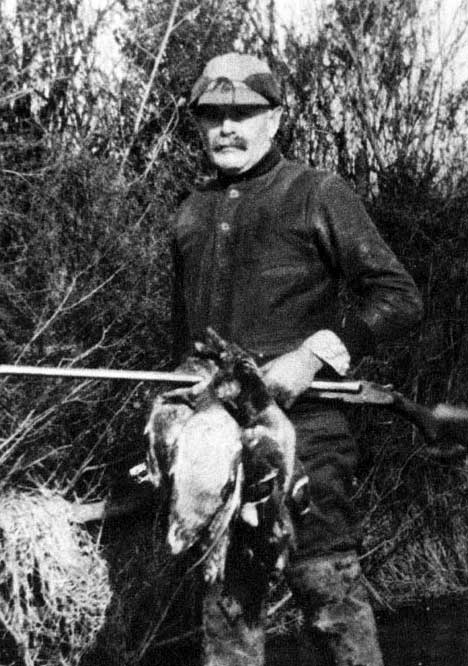

Charles Grubbs is arguably one of the earliest pioneers of modern duck calls. Born in Ohio in 1848, Grubbs made his way to the famed Illinois River Valley near Putnam in 1872 where he met his future wife, Amanda Hawkins. Grubbs started the Undercliff Hotel and Summer Resort along the shore of Lake Senachwine, a backwater lake along the banks of the famed Illinois River where he guided and hunted for the market.

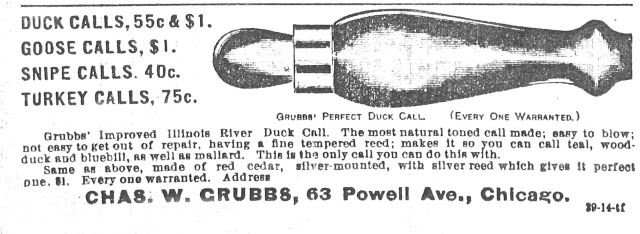

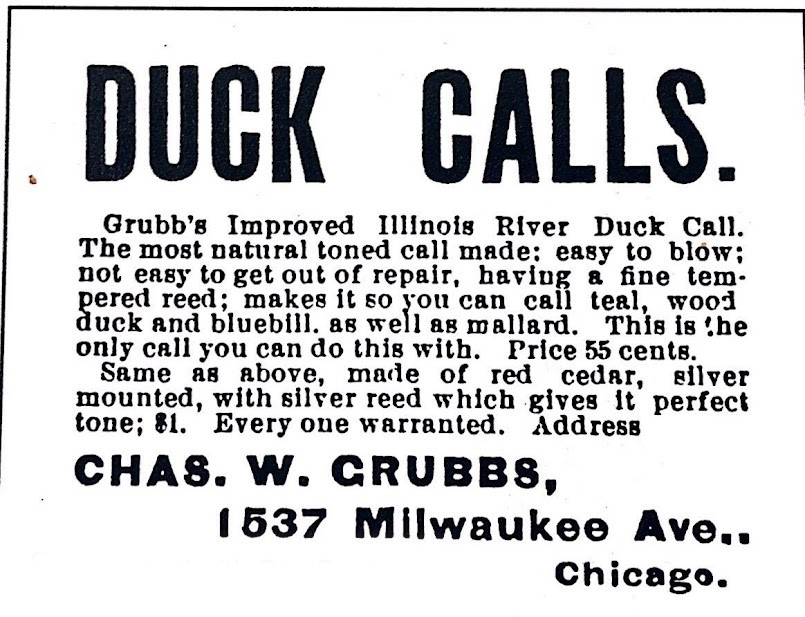

According to his own hunting catalog and testimony, Grubbs made the "first commercial duck call” that was available to the market in 1868. Early advertising for his calls can be traced back to the 1892 Montgomery Ward catalog. Grubbs's calls are the first documented metal-reed calls of what is now known as Glodo or Reelfoot Lake style. He made several different styles, which are historically speaking, the most important calls in existence. His calls were marketed by various sporting goods stores, such as Von Lengerke and Antoine (VL&A) in Chicago, and by Grubbs himself. Very few of Grubbs’ earliest calls have found their way into collections.

Grubbs was not known to stay in one location very long. At some point in the late 1880s, Grubbs lost control of the Undercliff Hotel and moved to Chicago to work at VL&A and The Fair, both of which were upscale sporting goods stores. During his tenure in Chicago, Grubbs continued to hunt and guide hunters along the Illinois River in the Hennepin area.

In 1916, Grubbs moved to Pascagoula, Mississippi, where he continued to make calls. In 1920, Grubbs, along with a couple of investors started producing wooden duck decoys under the name, “Grubbs Manufacturing Company.” Decoys made by Grubbs were in high demand and were soon being shipped all over the country.

Grubbs was somewhat of a decoy pioneer in the area and set the stage for many other area carvers. Because of Grubbs, the Pascagoula area became one of the largest producers of wooden decoys in the country. Unable to keep up with the demand, Grubbs sold his business to the Hudson Manufacturing Company in 1925. In 1926, he went to work for the Poitevin Brothers Decoy Company. During this time, Grubbs helped them develop a duck call for their lineup. On the outside, the new “Singing River” model duck call resembled Grubbs standard model call that he had been producing for many years but the toneboard construction was of the j-frame style that modern calls use. The Perfection Model calls that were made in Mississippi had the same style as his earlier made calls but they were larger in diameter. This business relationship lasted less than a year.

In 1927, Grubbs moved to Houston, Texas, where he continued making calls and decoys. His new business was located at 608 Gray Avenue in Houston. The business dealings he had with the Poitevin Brothers and others while in Mississippi must not have ended cordially. He boldly stated in a new catalog, “We are in NO WAY connected with any other company that makes decoys. WE ARE MAKING OUR OWN PRIZED-WINNING DECOYS, CALLS, AND GRASS BLINDS.”

Grubbs continued to make calls and decoys up until his death in August of 1933. Historic duck call makers such as Charles Perdew, Skippy Barto, Val Leonard and many others were influenced by Grubbs. His early calls are very rare and highly prized by collectors for their historic value.

You can see early examples of Grubbs' work from my collection that is on display at the Ducks Unlimited Heritage Center in Memphis at Bass Pro Shops Pyramid until September 2022. I can be reached at rkegraves@gmail.com and @rkegraves on Instagram.

Learn about other vintage duck call makers: