Tracy L. Schmidt | Originally published in GameKeepers: Farming for Wildlife Magazine

If you hunt ducks or geese, you probably know “Jack Miner” by his legacy: the metal waterfowl leg band, considered by many as a “trophy” among avid duck and goose hunters. He was also a man of faith and family. A man who deserves to be recognized as having left an ongoing legacy and not allowed to be left behind in history’s dusty pages. His name was Jack (John Thomas) Miner, and he is considered as the “father of American conservationism.” He was also known as “Wild Goose Jack.”

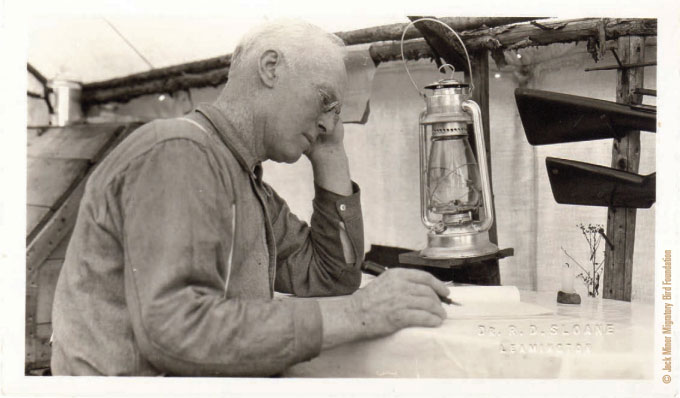

Miner was a man of profound thought who conveyed his convictions through a delicious simplicity. In the introduction to his 1923 book, Jack Miner and the Birds, and Some Things I Know about Nature, he explains that he decided to write the book himself in his own “untrained hand.” What is interesting is that this man, like many hunters, remembers the events of his hunts like milestones in life and retreats to the woods to share his thoughts in an almost Thoreau-like manner.

He intones that he was no devil but rather a God-fearing man. In 1915, he began using banded birds as “missionary messengers,” by stamping a scripture verse on what used to be the blank side of his aluminum wild duck and goose tags.

“To me, his pioneering efforts in waterfowl banding and subsequent data recovery are monumental,” said Brian Lovett, a waterfowling expert from Wisconsin and author of Innovative Duck Hunting. “He was one of the first — if not the first — person to complete a full banding record of a wild duck. Data from his early duck- and goose-tagging efforts became pillars of the first Migratory Bird Treaty, which is still a cornerstone of modern waterfowl management. And the foundation he established really originated the concept of waterfowl refuges.”

When you consider all the advances in GPS, radio-telemetry and other wildlife-monitoring technologies, it's amazing to think that Miner's bird-banding concepts still hold so much value, Lovett added. “And without refuges, we would not have the thriving waterfowl resources we enjoy today. It's critically important to give migratory birds places to rest and feed in relative safety during their long, perilous journeys.”

Family & Flights of Faith

sense that he taught us it is acceptable to harvest

waterfowl, but we must but also simultaneously protect and

increase their populations. He was a genius

conservationist.

Jack Miner was born April 10, 1865, in the state of Ohio. When he was thirteen his family moved to Canada, a “sportsman’s paradise,” where he was “liberated.” His family was large, as there were a total of ten children. He killed his first deer with small bullets he made by melting down his unknowing mother’s antique pewter spoon.

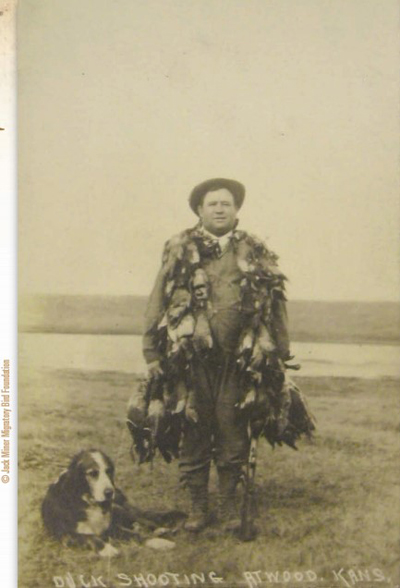

He became a trapper and market hunter to help support his family. Although, he later found it to be not much sport and tried to make amends through his waterfowl conservation efforts.

“He was a hunter who paid attention to his impact on nature,” and in fact, seemed to take to heart a line he quoted in his 1925 note in Jack Miner and the Birds: “Let man have dominion over all.” For Jack Miner that meant not only to take, but also to simultaneously protect and increase wildlife populations and timbers.

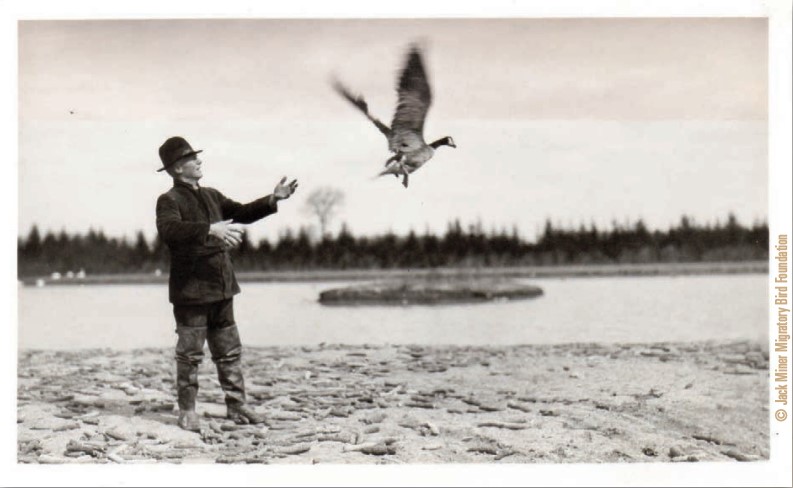

Miner’s interactions with birds and his observations of their interactions with each other led him to found the Jack Miner Migratory Bird Foundation during 1904. The purpose of the foundation was to provide a waterfowl conservation management system for migrating Canada Geese and wild ducks. It was meant to protect these birds not only from over-hunting by man, but also from predation by other wildlife. It took four years and finally in 1908, the first of eleven migrating Canada Geese felt comfortable enough with the pond he created to land. During 1909, he banded his first wild duck and his first band was returned to him in 1910.

Data compiled from tagging recoveries was vital in the 1916 Migratory Bird Treaty between the U.S.A. and Canada. The first restrictions on hunting, taking into consideration future waterfowl populations were defined by this Act.

Living Legacy

This primarily, formally “unschooled” fellow went on to help found the Outdoor Writers Association of America at an Izaak Walton League conference on April 9, 1927 in Illinois. He was the first Canadian presented an Outdoor Life Gold Medal "for the greatest achievement in wildlife conservation on the continent."

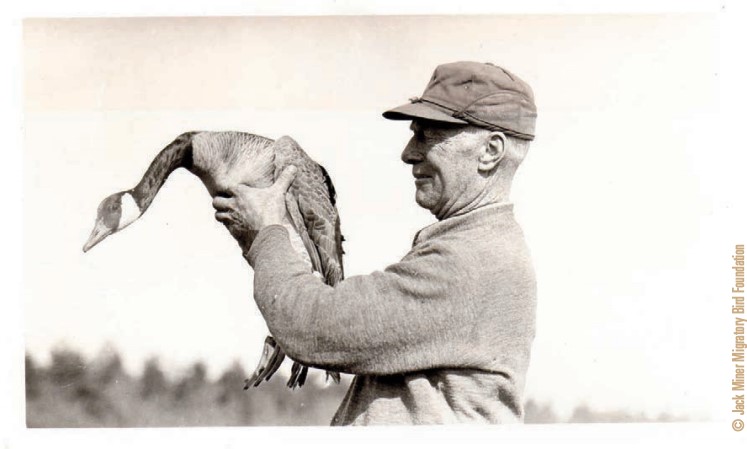

He was presented with the Order of the British Empire "for the greatest achievement in conservation in the British Empire," by King George VI the year before he died in 1943. According to The Jack Miner Migratory Bird Foundation, at the time of his death he had been responsible for the banding of over 50,000 wild ducks and 40,000 migratory Canada geese.

These are remarkable achievements that reflect the life-long knowledge of a man who devoted himself to the observation of life beyond himself. According to Mary E. Baruth, executive director of the Jack Miner Migratory Bird Foundation, the founder’s message of conservation is more important now than it ever was. “The Jack Miner Migratory Bird Foundation continues the work of Jack Miner by banding and recording the data reported during band recoveries,” she said. “It also works with agencies to study migration patterns and tracking devices such as GPS bands, etc.

“The Foundation continues to promote the message of conservation to visitors and to school children through special events, curriculum, and educational programs. It also continues to partner with a variety of groups and businesses to preserve and expand upon its mandate.”

The Jack Miner Migratory Bird Foundation is international - it was established in 1931 in the United States and in 1936 in Canada to continue the good work of Jack Miner, to protect and improve the Sanctuary and Jack Miner property. The Foundation is a charitable organization that operates solely on grants and the generosity of private and corporation donations from the USA and Canada. The Board of Directors and staff are responsible for the ongoing operations of the Foundation.

“We owe Jack Miner a huge debt of gratitude,” Lovett added. “So much has been learned by his work. Critical management information, including survival and hunter harvest rates, in addition to bird-banding info has helped scientists define the migration routes and patterns of migratory birds. Just the idea that this simple concept continues to be so valuable speaks to its genius.

“On a personal level, it's always a thrill for a hunter to take a banded bird. When you “call in the band” and receive the history of the bird, it just adds to the mystique of waterfowl hunting. A goose might have been captured and banded five miles from where you shot it or thousands of miles away in Hudson Bay. It's just neat to learn more about that animal.

“You still see his name mentioned quite a bit in waterfowl circles, mostly when a hunter recovers a bird that was banded by the foundation Miner founded,” he said. “These "Jack Miner bands," as they're known among hunters, are pretty cool, as they contain a brief verse of scripture. I think many folks really relate to the link Miner saw between his scientific research and spirituality.”

Worthy Not To Be Lost

In History Despite Miner’s lasting legacy, he is not always first to mind among modern conversations on important issues surrounding waterfowl and waterfowl conservation. His legacy is ongoing and deserves to be discussed and recognized today.

“What escapes some folks is how famous he was in the day,” said Lovett. “When he died, (1944) several papers ranked him as the fifth-best-known man in all of North America - behind people such as Henry Ford, Thomas Edison and Charles Lindbergh. He had been called "the father of conservation" and received the Order of the British Empire.”

“He also had some pretty strong and perhaps odd views about predatory animals. He hated crows and raptors, even calling the latter "murderers" because they often preyed upon the birds — ducks, geese, quail, pheasants — he admired so much.”