Brent Rogers

The will to live is incredibly strong in wild turkeys, and many a jilted hunter has endowed their feathered opponent with super-human abilities. Many stories are passed down about gobblers that are tricky, cagey, wily, or wise. It may surprise you to learn that the American literary master Mark Twain penned a short story Hunting the Deceitful Turkey that many a modern day hunter can yet relate to.

Hunting the Deceitful Turkey first appeared in the December 1906 issue of Harper's Magazine - a premiere journal of the day with an international audience. Of interest to wild turkey literature enthusiasts, keep in mind this story was published more than a decade prior to the first book dedicated to wild turkey hunting, which was largely written by Charles Jordan and published in 1914 by Edward A. McIlhenny after Jordan’s tragic death at the hands of a poacher. Certainly, there were many other magazine articles about wild turkeys that predated Twain’s story, but how neat that such an article appeared at a time, and in such a notable journal, when turkey hunting was near a mythology.

Samuel Clemens was raised near Hannibal, Missouri, and had to seek work at the tender age of 11 following the death of his father. After working on riverboats in the Mississippi River, he assumed the pen name "Mark Twain" - cleverly the term riverboat Captains used to mark safe passage at a depth of two fathoms (12 feet). You are not alone if the name "Twain" brings Huck Finn to mind instead of turkey hunting. Though not an avid hunter, in his autobiography he writes fondly of 3 summers he spent at his Uncle Quarles’ farm in northeast Missouri. His maternal uncle and cousins apparently introduced him to the pursuit of the wild turkey; their farm is the setting for his story. By no means am I qualifying Twain as a turkey hunter, at least not the obsessed type of turkey hunter that normally is driven to share their grand days afield. The significance here is the meeting of two American icons, Mark Twain and the American Wild Turkey, and for once, Twain meets his match in a battle of wits!

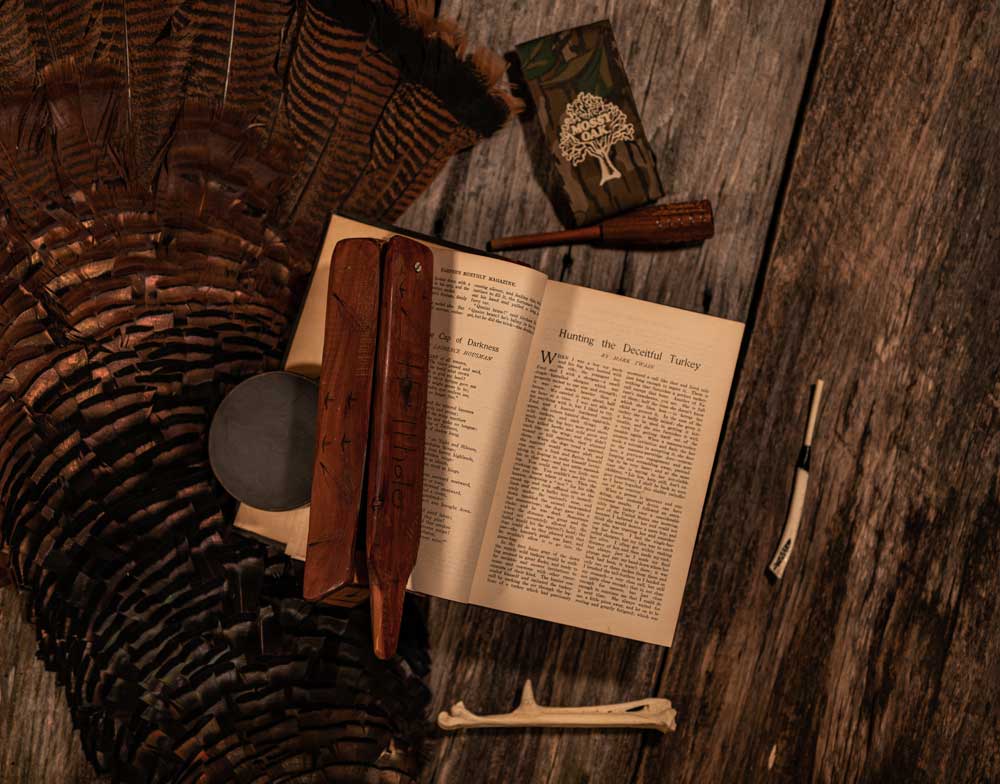

Twain is known for his satirical brilliance, and he writes of turkey hunting in the same tongue-in-cheek way. He finds some ironic humor in the fact that “The hunter concealed himself and imitated the turkey-call by sucking the air through the leg-bone of a turkey what had previously answered a call like that and lived only just long enough to regret it.” Whether using a leg-bone or the more familiar wingbone, there is indeed some ‘treachery’ as he aptly says, in the use of one turkey’s body part to fool another! We can thank Native Americans for that bit of ingenuity, as they are credited with using wingbones for centuries before the arrival of Europeans. I employ wingbones as regular part of my calling arsenal, including those I make myself. I find it a great way to honor the bird through using more of the body it sacrificed, and makes a nice gift for landowners or friends, let alone usefulness in the woods.

WATCH: Making a Wingbone Call - The Specialists

Twain emphatically endorses the wingbone, saying “There is nothing that furnishes a perfect turkey-call, except that bone.” While many hunters and call makers know how effective calls of wood, cane, slate and a myriad of other materials can be, there is something deeply satisfying in using a well-crafted wingbone. The piping calls of a well-tuned ‘bone produce excellent tonal quality and the ability to carry over some distance. In Larry Proffit’s excellent turkey hunting book Letters To My Grandsons, he shares how his recording of wind-instruments at a distance helped him establish their superiority over many other calls. If you know, you know!

Real hunters enjoy the hunt, and have a reverence for that special time of day when the sun rises and the natural world transitions from dark to dawn. Twain captures it in his story by writing “In the first faint gray of the dawn the stately wild turkeys would be stalking around in great flocks.” Man…if that doesn’t bring to mind fond memories of days chasing birds! Given Twain spent summers at his Uncle’s farm, this seems to have been a fall hunt given his descriptions of the vegetation…after he returns famished and empty-handed he sates his hunger in a “weed grown garden…full of ripe tomatoes.” Sounds better than the tag soup!

Twain captures well the hopelessness and exhaustion one feels after a long day of getting your butt handed to you in the turkey woods. He reportedly hunted this turkey for ten hours over what seemed “a considerable part of the United States.” Oh yeah, we have all had those days! Taking those lickings is a part of the turkey hunting experience that makes the ones that ride home over the shoulder even more special. We all appreciate when a turkey lands in our lap at fly-down time, but turkey hunting would lose its allure if not for the chess match of moves and counter-moves that creates an appropriate respect for our feathered adversary.

Elsewhere, Twain has been quoted as saying “Do not tell fish stories where the people know you; but particularly, don’t tell them where they know the fish.” Ha, indeed! The telling of stories is definitely one of the greatest traditions of sportsman; it is how we honor the quarry…and expand on the greatness of our exploits! I suspicion his Uncle and cousins probably had a good working knowledge of turkey hunting, but Twain’s lack of experience is evident in how he writes about the hunt and lends to his empty game bag. His reference to deceitful behavior is implied as trickery from the hen turkey he was pursuing. He says had it a limp, which he came later to believe was just to deceive him. At one point, he observes the turkey “lay on her side fanning herself with a wing” which he also interpreted as behavior to lead him away from her young. It is more likely he was witnessing her dusting. Though hens are legal fall birds in some states, the fact he was pursuing a hen is probably less related to the season than the general pursuit of all turkeys. Turkeys were turkeys, and good table fare. Hunting regulations were not largely developed as we know them.

At the time of this story, the American wild turkey was in decline. By 1920, they had disappeared completely from 18 of 39 states they originally occupied. The nationwide estimate of the population at the time ranges from 30,000 to 200,000. In Twain’s home state of Missouri, the Missouri Department of Conservation (MDC) estimates there were only 2,500 turkeys remaining in the state. In 1954, Missouri started trapping and relocating wild turkeys within the state. The 2021 Missouri spring turkey season harvest was 34,593 with and addition 3,192 taken in the fall season, truly a conservation success story. But…as turkey hunters know, we are once again facing questions we need research to answer, as the 2021 spring harvest is down about 7,000 birds from 2020. MDC estimates the population peaked at about 600,000 birds in the early 2000’s and has since shrunk by nearly half to about 350,000.

I encourage you to read Twain’s full story, and you are in luck, as the copyright is long expired. A Google search for the article will reward you. In 1984, June Bernier re-published this quaint story in the form of a hardback micro-miniature book, barely larger than a U.S. quarter. In a practical sense, micro books were popularized prior to computers and digital files, and were travel friendly. In any case it is a unique publication of a vintage story. The micro book is limited to a signed (by Bernier) and numbered edition of 150, complete with added illustrations that were not part of the original Harper’s Magazine article.

I find it fascinating that where Twain was humbled by a turkey is just an hour’s drive from where I myself travel to hunt wild turkeys in the Show-Me state. I’ve had a small amount of success there, along with a healthy dose of humbling. And a bit further south, how appropriate that one can today wander the 1.5 million acres of the Mark Twain National Forest in pursuit of the wild turkey. May you continue to admire the uncanny ability of this wonderfully ‘deceitful’ American bird to outwit and outmaneuver you!